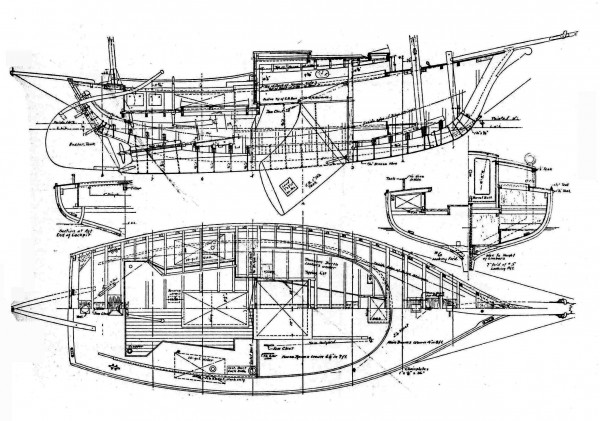

We lost a good man when Joel White died in 1997—and an exceptional boatbuilder. His clear thinking and writing shows here in a piece he wrote for WoodenBoat No 87 and which his wife, Allene, has kindly allowed OCH to share with its members. We doubt you’ll find a better rundown on getting together what you need to build a traditional wooden boat. Joel built this 20′ Crocker sloop (used as his wood-ordering example) in 1967 for his father E.B. White who named the boat MARTHA after his grand-daughter. The boat now belongs to WoodenBoat School director Rich Hilsinger who keeps her well and uses her often.

Here is what Joel had to say about ordering wood:

Ordering lumber for a boatbuilding project often seems to be a problem for boatbuilders, whether amateur or professional. Many come to a halt when confronted with the need to produce a lumber list from a set of boat plans. It takes some practice to look over the designer’s drawings and compile a lumber list, with quantities, from which one can build a boat. Sometimes a set of plans will include a lumber list, but it is always advisable to check it over before ordering. Some builders are not familiar with lumberyard practice and terms, and feel shy about asking a lumber dealer what might seem to be a silly question. Here’s how to go about getting the wood you need:

Let’s talk a bit about sources for lumber, before getting into the specifics of ordering. I would break down the sources as follows:

•Local lumber from local mills.

•Domestic lumber from local building-supply outlets.

•Domestic and imported timber from lumber dealers.

•Other sources—logs cut and milled by you, other people’s boatbuilding projects gone sour, drift logs, driftwood, etc.

Any or all of these sources can be used to acquire the wood you need to build your boat. For instance, here in the East, the backbone and the planking material for the boat under construction might be oak and cedar obtained as live-edge (flitch-sawn) stock from your local lumber mill; the molds and ribbands would be built from spruce planks obtained at the nearest building-supply house; and the mast might be a tree cut on your own land behind your house, and four-sided with a chainsaw right in the woods. The mahogany for the stern and cabin sides, to be finished bright, might come from a specialty lumber dealer.

Lumber Nomenclature

Lumberyards and lumber dealers use slightly different language to describe timber than most of us are accustomed to. For instance, thickness is given in quarters of an inch: 1”-thick lumber is called “4/4” (said “four-quarter”), 1-1/4” lumber is called 5/4 (said “five-quarter”), and so on up through 16/4. Above this thickness, it is more common to talk of 6″ thickness or 8″ thickness. Width of lumber is normally described in inches, and length in feet. So a piece of timber 1-1/2″ thick by 9″ wide and 12′ long would be written as 6/4 x 9″ x 12′.

When buying more than a few pieces of lumber, it is usual to specify the quantity needed in board feet, and to purchase under the designation “RWL” (this stands for “random width and length”). Thus, an order for 200 board feet 5/4 RWL Honduras mahogany would produce a nice pile of mahogany boards 1-1/4” thick, of varying widths and lengths. A board foot of lumber is 1 square foot of timber 1″ thick (or half a square foot 2″ thick).

A word of caution here: Lumber thickness is always given in the rough, just as it comes from the saw. Thus, to get finished (planed on both sides) lumber 1″ thick, you must order 5/4. Allow a minimum of ¼” thickness for dressing lumber to its finished thickness. If the lumber is accurately sawn, with little variation in thickness throughout its length, you may be able to do a bit better than this, but you cannot count on it. If you do not have a planer, or access to one, most lumberyards will supply your lumber planed to any thickness you specify, but you will be paying for the rough thickness from which it was milled, plus a fee for the milling.

Another thing to remember: Your building supply outlet will deal mostly in dimensioned lumber— like 2 x 4s, 2 x 10s, etc., which will actually measure 1-1/2 x 3-1/2” and 1-1/2 x 9-1/2” respectively. Length of dimensioned lumber is in even numbers of feet—8′, 10′, 12′, 14′, 16′. So, try to adjust your order to accommodate these dimensions. Many building supply outfits, however, will supply lumber sawn to your specifications.

Species

The sawmill or lumber dealer will need to know what species of tree you seek. Mostly, this is straightforward. White oak, Northern white cedar, Southern cedar (often called Virginia white cedar), ash, cypress, Eastern white pine, Sitka spruce, teak, and the many varieties of mahogany will be carried by a well-stocked lumberyard, plus a number of other species not generally known as boatbuilding woods. Some timbers will be domestic; others are imported. Most boats are built using some of each. As a general rule, imported lumber will be higher priced than domestic, but demand and availability really determine the price.

Confusion may arise when there are several names given to the same species. An example is yellow cedar and Alaska cedar; as far as I know, this is the same tree with two different names. Hackmatack is often called “tamarack” or “larch,” and there are a dozen or more different species that are all sawn into “Philippine mahogany.” If you are going to use Philippine mahogany, specify “dark.”

Grade

Trying to understand the grading of lumber for quality leads to a real morass of terms, and standards seem to

vary from company to company, country to country. Rather than get both of us into an area of confusion, my advice to you is to find a lumber dealer you can talk to, tell him what you are trying to build, what is needed for quality, and he will tell you what he has and how much it will cost. Most lumber dealers who handle boat timber are aware of the quality needed and try to stock such timber. I find it helpful to explain how the material will be used. If you need clear white oak for steam-bending frames, specify that it come from clear, straight-grained butt logs. Honduras mahogany often can be had in either straight-grained or more heavily figured stock. The wild-grained lumber may make a handsomer cabin table, but the straight-grained will be better for planking.

It is sometimes possible to specify whether you want flat or vertical grain. Another variable that enters into the quality of your lumber is its dryness, or lack thereof. Most lumber obtained from a specialty lumber dealer will be dry, often kiln-dried. Some outfits handle both air-dried and kiln-dried timber. In general, air-dried is preferable for boatbuilding use. If you go to your neighborhood sawmill and order material sawn from the log, it will be pretty green. For the backbone stock, this is perfectly satisfactory. These items will be, for the most part, underwater, and will swell and shrink less if green rather than if dry. In truth, it is not feasible to completely dry large oak timbers. Trying to do so would only result in the timbers twisting and checking to such a degree that they would become unusable. A couple of coats of red lead on the backbone structure after assembly will prevent the green oak from drying and checking too much while the boat is under construction. Planking stock, on the other hand, should be obtained far enough in advance of building to allow it to be well air dried before use.

Plywood

You may or may not use some plywood in your boatbuilding project. Here are a few facts that will help when ordering plywood. The standard panel size, even for imported plywood, is 4 x 8’. Sometimes 10’ panels are available on a limited basis. If you must have longer sheets, these can be ordered custom scarfed, or you can do it yourself. Standard thicknesses are ¼”, 3/8”, ½” and ¾” (or the equivalent in millimeters); other thicknesses, both thinner and thicker, are sometimes available. The test of quality in plywood is the number of plies and the absence of interior voids. A high-quality ¼” panel will have five plies, a less-good panel only three. The best ¾” panels will have thirteen plies, a less-good panel only seven. I would recommend using only marine-grade plywood, as exterior grades contain an unacceptable number of voids. Any void is unacceptable, except for cabin joinerwork, and if the edge-grain of the plywood is to show, voids won’t do there, either. Most foreign plywood is measured for thickness in millimeters (6mm is just under ¼”, 9mm just under 3/8”, 12mm just under 1/2”, and 18mm just less than ¾”). High-quality panels should have all plies of equal thickness. Sometimes you see plywood with thick core plies and thin face veneers; avoid these, except perhaps for cabin furniture. Quality of the face veneers is designated as A, B, C, or D—A being the highest and D the lowest. Thus, an “AA” designation means both face veneers are of best quality, while “AC” or “AD” means one good face, and the other not so good. Some large lumber dealers handle marine plywood, some do not There are a number of companies that deal only in plywood panels, and these companies usually have the largest inventories and the best selection of panels.

Estimating Quantity

We will now go through the process of making up the lumber list needed to build a boat. Let’s use as an example the nice little S.S. Crocker design No. 300, a 20′ overall centerboard sloop (or yawl). More than 20 years ago I built one of these dandy little boats, so I happen to have the plans and specifications on hand, and some remembrance of what is needed for materials.

We will now go through the process of making up the lumber list needed to build a boat. Let’s use as an example the nice little S.S. Crocker design No. 300, a 20′ overall centerboard sloop (or yawl). More than 20 years ago I built one of these dandy little boats, so I happen to have the plans and specifications on hand, and some remembrance of what is needed for materials.

. . . sign up to the right to get immediate access to this full post,

plus you'll get 10 of our best videos for free.

Get Free Videos& Learn More Join Now!!for Full Access Members Sign In

mike Brown says:

a clear explanation of where the timber is used , losses in trim and wastage are not usually allowed for when ordering. We all like to keep the cost down at the beginning as a lot of tome is absorbed with setting up a backbone, locating frames etc. it is easy to under allow for waste

Enrique Bruna says:

I’m from Chile, in the southwest extreme of America, and I find me understanding the descriptions of lumber needs for these boat, perfectly. But not because I understand so well your english, but for I was a lumber yard owner and I love boats from my early years.

I have study some plans of Joel White, and I agree with the frequently asserts that describe him like a gentleman and a careful designer. It is a great gentleness to give us such a complete list and so fine description!

pablo besser says:

hola enrique, aca otro chileno disfrutando esta pagina. tambien aficionado a construir veleros de madera. de santiago? se contruyo alguno de esos planos.

mi correo es pbesser@gmail.com saludos.

ramon rodriguez says:

I love listening to Joel White as he reads selected portions of his father’s work.

David Tew says:

Joel’s writing is direct, correct, and delightful.